This piece was published in FishFirst, May 2022 edition

Author: Dr Brett Glencross

WHAT IS 30 BY 30?

Human exploitation of our oceans has long been recognised as having significant consequences for its ecosystem health, though clearly some activities are more damaging than others. One of those exploitive activities that has come under increasing scrutiny over the past twenty years are fisheries. Various strategies to minimise ecosystem effects of fisheries have been implemented over that time, but among the more prominent and contentious of late are the use of marine-protected-areas (MPAs).

In recent years there has been a growing call for “30 by 30” as a global initiative to designate 30% of world’s ocean area as a MPA by 2030. The target of 30% was originally proposed in an article in Science "A Global Deal for Nature", published in 2019, where in that paper the authors highlighted the need for increased conservation efforts to mitigate climate change. The proposal was launched in 2020, and more than 50 nations had signed on to the initiative by January 2021 which had expanded to over 70 nations by October.

WHY 30 BY 30?

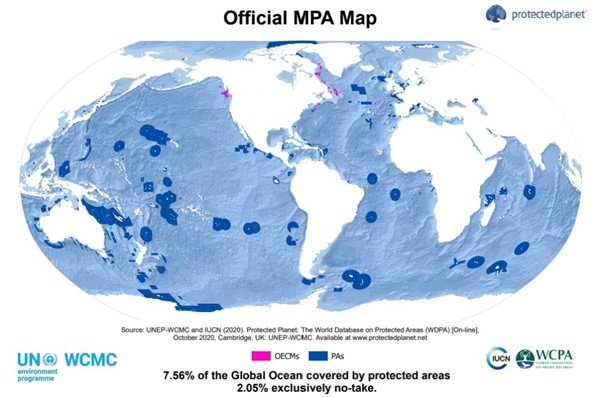

Globally, just a little under 8% of the world’s ocean has a significant degree of protection, and of that a little under one third has been designated as no-take areas (Figure 1). Over the past 20 years various governments around the world have created MPAs of various means and dimensions. For example, in 2010, the British government set aside a large part of its Indian Ocean Territories, at the Chagos Archipelago, as an MPA. Consisting of almost 650,000 square kilometres, the new MPA was one of the largest protected areas anywhere on Earth at that time. It was claimed that it was an area that was subject to increasing fishing pressure from vessels operating on the high seas.

But was the protection effective in making any difference? An assessment in 2020 of the ecosystems of the archipelago found that sea turtles had become more abundant and that nesting seabirds were also thriving, with coral cover now as high as 50 per cent of reef surfaces. So, while the use of an MPA strategy was largely succeeding on one front, the assessment also highlighted that illegal fishing was still happening despite the introduction of the MPA and that in the process a legitimate tuna fishery and many of the artisanal fisheries of the locals had been lost.

However, it has been argued that MPAs offer a range of other important benefits to broader society. It has been estimated that almost a third of the world’s population depend either directly or indirectly on marine and coastal biodiversity for their livelihoods. Oceans are also a major carbon sink and play a critical role in slowing climate change.

HOW WILL IT AFFECT FISHERIES?

It has been suggested that most oceans are poorly managed. The FAO SOFIA 2020 report indicates that of almost 5000 global fisheries, that overfishing had left less than a third of those fisheries in good condition. Global climate change and pollution now threaten many fisheries and their supporting marine ecosystems throughout the world. Notably, climate change is making waters warmer, more acidic and lowering oxygen levels, and many species are redistributing to more suitable areas. Analysts predict that in the long term there will be winners and losers from this redistribution, but overall, there will be a net loss.

Some experts contend that increasing the area of MPAs to 30 per cent of the ocean will make a big difference. They also contend that fishing can be banned in those MPAs and that in the long run, that this will help fishing communities. This notion is based on the idea that fish populations rebound inside the protected areas, before they spill over into nearby fishing grounds, ultimately boosting catches. For some demersal fisheries there is evidence to support this, however, for pelagic species the evidence is not so strong as these species rarely rely on specific localised ecosystems and would move in and out of potential MPAs undermining their benefit to those fisheries. Recent studies published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) suggested that a 20% improvement in future catch could be achieved by increasing the total MPA area to over 10%, although a subsequent retraction of that study demonstrated how such models can be fraught with error if some simple assumptions are incorrect.

Crucially, the benefits of MPAs are more constrained to those coastal ecosystems where human impact is already the highest and often not from fishing, but a suite of other pollution and climate change factors. This is where any MPA target needs to focus on, however those areas are more politically sensitive as they directly impact the majority of the population. What is needed is a way of magnifying the benefits of any MPAs by protecting the most sensitive ecosystems and those with the greatest potential to be carbon and biodiversity reservoirs. Such an action as this would deliver benefits across the whole of the ocean, without affecting those whose impact is already relatively light.

DOES SIZE REALLY MATTER?

While simplistic targets can focus political will, the size of MPA is not necessarily as important as the ecosystem of the MPA. In some sense, it is not the size that matters, but what is represents that is important. Governments the world over have continued a trend toward larger, more remote MPAs, largely as a means to achieve arbitrary international targets, but for the most part they are not really protecting much of anything. Much of the areas they are protecting are open ocean ecosystems which are not the ecosystems principally at threat and those elements that might be protected from such areas (e.g. pelagic fisheries) are so transient that the protection is only limited at best and better served by other regulatory mechanisms such as quotas and fishery regulation and monitoring.

Indeed, such remote open ocean MPAs are most likely missing their intended mark. Recent studies published in Nature Ecology & Evolution pointed out that the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets need to do more than simply setting aside protected areas. Such MPAs need to be “equitably and effectively managed,” they need to be “ecologically representative” and “interconnected” to each other to have any impact on reducing biodiversity loss. Importantly, this notion of “equitably and effectively managed,” doesn’t mean locking it up and keeping everyone out, but rather regulating the impacts on a sustainable and equitable basis. Based on those measures of being effectively managed, representative, and interconnected, most existing MPAs are failing at what they intended to deliver.

WHY 3% COULD BE BETTER THAN 30%

Whether we set aside 3 percent of our oceans, 10 percent or even 30 percent, scientists and policymakers are arguably shuffling deckchairs on the Titanic around the edges of the real drivers of ecosystem decline – climate change. A 2019 study in Nature – Scientific Reports on the key drivers of human impacts on marine ecosystems demonstrated that the cumulative impacts of climate change related drivers were so dominant, that other factors like fishing activities were largely inconsequential. The study also showed that some ecosystems, like coral reefs, seagrass, and mangroves were far more susceptible than others. Highlighting a need to target any management on specific ecosystems rather than blanket entire areas.

Like many of the major issues of our time, the science is complex and there aren’t simple solutions. Because of this, these problems need vast amounts of money and political will, both of which appear to be in short supply. Consequently, conservationists are left fighting over scraps and political compromises, and they end up recommending politically soft targets like industrial fisheries. However, if we really want to maintain biodiversity and ensure a variety of healthy ecosystems in our oceans that sustain a wide range of services that oceans sustain like; food production, CO2 absorption, climate regulation and so on, then this higher percentage is not necessarily the answer for long-term impact, but rather we are better focusing our use of such tools on areas of high ecosystem value.

So, to ensure we make the best possible decisions into the future, those that help maintain the maximum biodiversity, increase the value of the various ecosystem services that oceans provide, then more investment in monitoring and developing a clear decision framework linked to specific goals is required. In this way, the limited resources the world is willing to set aside for our oceans will buy maximum value. MPAs need to be sited where they can make the most difference, not where they are politically expedient.

Figure 1. Map obtained from https://www.protectedplanet.net/en/thematic-areas/marine-protected-areas

Figure 2. Coral reefs like this one in Vietnam represent some of the most vulnerable marine ecosystems on Earth, where use of MPAs has some clear benefits. Photo: B.Glencross

Cabral, R. B., Bradley, D., Mayorga, J., Goodell, W., Friedlander, A. M., Sala, E., ... & Gaines, S. D. (2020). A global network of marine protected areas for food. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(45), 28134-28139.

Curnick, D. J., Collen, B., Koldewey, H. J., Jones, K. E., Kemp, K. M., & Ferretti, F. (2020). Interactions between a large marine protected area, pelagic tuna and associated fisheries. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7, 318.

Costello, C., Ovando, D., Clavelle, T., Strauss, C. K., Hilborn, R., Melnychuk, M. C., ... & Leland, A. (2016). Global fishery prospects under contrasting management regimes. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 113(18), 5125-5129.

Dinerstein, E., Vynne, C., Sala, E., Joshi, A. R., Fernando, S., Lovejoy, T. E., ... & Wikramanayake, E. (2019). A global deal for nature: guiding principles, milestones, and targets. Science advances, 5(4), eaaw2869.

FAO. 2020. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020. Sustainability in action. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9229en

Halpern, B. S., Frazier, M., Afflerbach, J., Lowndes, J. S., Micheli, F., O’Hara, C., ... & Selkoe, K. A. (2019). Recent pace of change in human impact on the world’s ocean. Scientific reports, 9(1), 1-8.

O’Leary, B. C., Ban, N. C., Fernandez, M., Friedlander, A. M., García-Borboroglu, P., Golbuu, Y., ... & Roberts, C. M. (2018). Addressing criticisms of large-scale marine protected areas. Bioscience, 68(5), 359-370.

Ovando, D., Caselle, J. E., Costello, C., Deschenes, O., Gaines, S. D., Hilborn, R., & Liu, O. (2021). Assessing the population‐level conservation effects of marine protected areas. Conservation Biology, 35(6), 1861-1870.

Sala, E., Mayorga, J., Bradley, D., Cabral, R. B., Atwood, T. B., Auber, A., ... & Lubchenco, J. (2021). Protecting the global ocean for biodiversity, food and climate. Nature, 592(7854), 397-402.