This article was first published in International Aquafeed magazine, November 2022

Author: Dr Brett Glencross

One of the criticisms we often hear about fishmeal and their underpinning fisheries is that they are “unsustainable” and that “the growth of aquaculture is driving further exploitation of fisheries”. But how true is this, what does the data say, and importantly what do the fisheries NGOs say about all this?

One of the criticisms we often hear about fishmeal and their underpinning fisheries is that they are “unsustainable” and that “the growth of aquaculture is driving further exploitation of fisheries”. But how true is this, what does the data say, and importantly what do the fisheries NGOs say about all this?

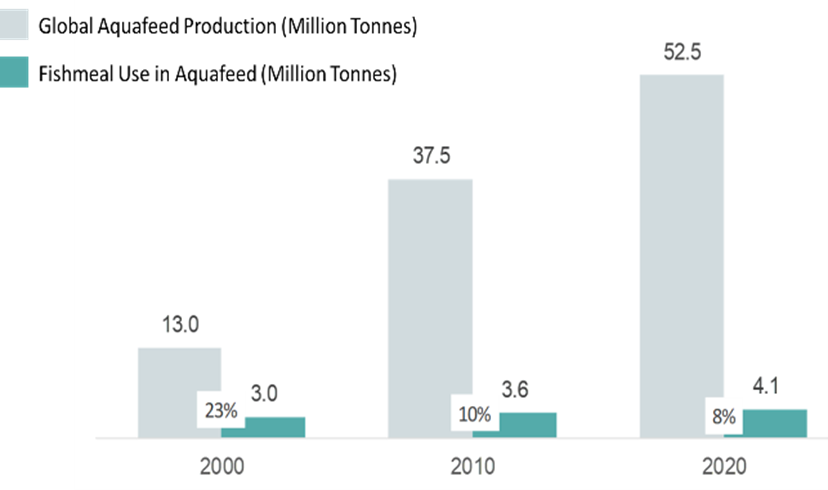

Let’s start with addressing the second point first. If aquaculture was driving further exploitation of fisheries, then with the growth of aquaculture over the past twenty years from using feed of around 13 MTonnes in the year 2000 to the year 2020 when it used over 52 MTonnes, we should have seen a four-fold increase in the use of fishmeal. But we didn’t, in fact fishmeal use by aquaculture only increased from 3.0 MTonnes in 2000, to 4.1 MTonnes in 2020 (Figure 1).

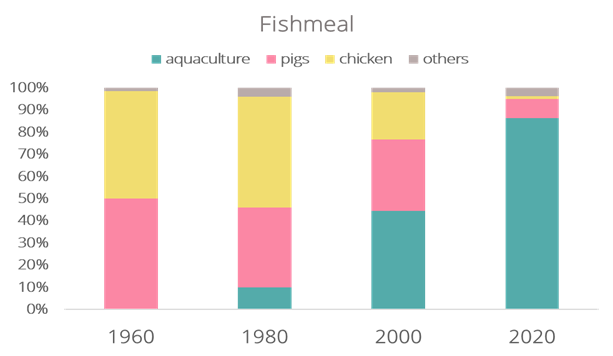

So, what happened to aquaculture “driving further exploitation”? The answer can be seen from a combination of figures 1 and 3. Although fishmeal use by the aquaculture sector between 2000 and 2020 increased from 3.0 MTonnes to 4.1 MTonnes, this meant that the proportional inclusion across the sector went from 23% down to 8%. So clearly the big proportion (over 90% of it in fact) of aquafeeds in the present day is not marine ingredients, and the sector has learnt to use a much broader range of ingredients. The other part of the answer is that the less (feed) efficient animal production sectors of pigs and poultry were unable to compete for the use of fishmeal, so the resource was diverted to aquaculture, which allows a much more efficient transfer of those marine nutrients in fishmeal into our food chain. Arguably a positive outcome from the use of the same volume of fishmeal.

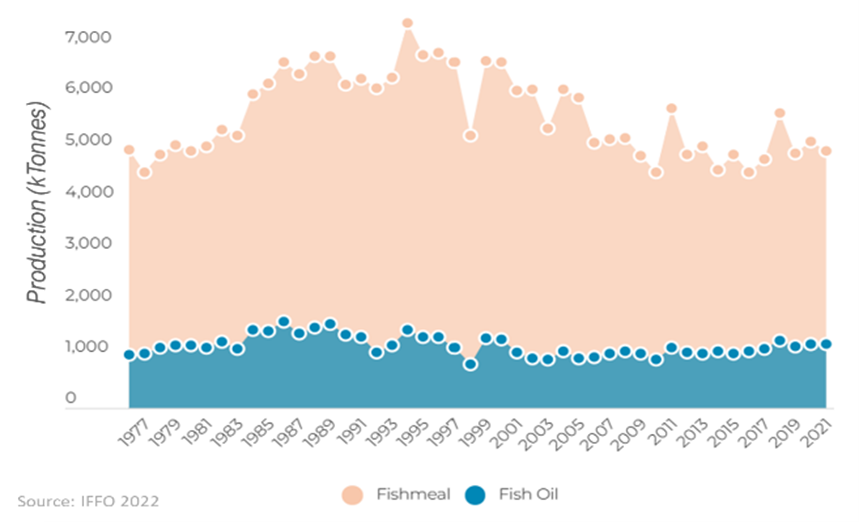

But what of that first question about those fisheries being used to sustain that production of 5 MTonnes of fishmeal each year? Well firstly, in 2020 we need to note that about 30% of global fishmeal production now comes from by-products from fish caught or grown for direct human consumption (DHC). So that means only 3.5 MTonnes of fishmeal presently comes from forage (reduction) fisheries. Using the industry standard yield of 22.5%, that means about 15 MTonnes of fish is harvested each year to produce that fishmeal. From that 15 MTonnes, a review of the FishSource Scores data on reduction fisheries from the eNGO Sustainable Fisheries Partnership’s (SFP) website, shows that the 24 main global stocks used for reduction purposes in 2019 accounted for about 10 MTonnes of harvested fish. Of those fisheries, more than 79% of the volume was deemed to have come from well managed fisheries. But of the other 21% of that 10 MTonnes, notably the loss of the MSC certification from the north Atlantic Blue Whiting fishery meant that this could have been 94% had there be agreement amongst the relevant coastal states on quotas.

So, from a fisheries management perspective, the sustainability score looks reasonable, but could certainly be better. Alas as can be seen from the Blue Whiting situation, often this a political issue, not so much a fisheries issue. Now only if we could manage politicians as (comparatively) easily as we do fisheries…

Figure 1. Global production of aquaculture feed and fishmeal use by the aquaculture sector from 2000 to 2020.

Figure 2. Global production of fishmeal from 1976 to 2021.

Figure 3. Global use fishmeal use by sector from 1960 to 2020.