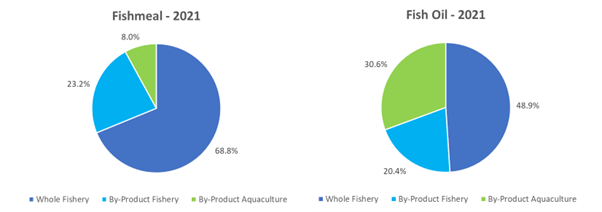

With more than half of all of global fish oil production and about a third of global fishmeal production coming from fish by-products in 2021 (IFFO data), the use of trimmings and by-products is clearly gaining momentum as a burgeoning circular feed ingredient (Figure 1). This age-old practice consisting in repurposing unutilised resources is reinforced by the growth of the aquaculture sector, now a major player in the provision of fish-based raw materials. The adoption of circular thinking is encouraged by environmental regulations supporting the use of low-carbon footprint resources. Capturing the full value of fish capture in our food chain also represents one of the best ways to ensure food security and combat food waste, which is key to meeting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) number 2 (Zero Hunger) and 12 (Responsible Production and Consumption) and halving global food waste by 2030.

On 23rd October 2023, IFFO held a technical workshop in Cape Town, South Africa, with ten scientists and industry representatives focusing on the utilisation of fish by-products and explored a range of topics including:

• How do we incorporate the circularity thinking more deeply in resource use?

• What is the most strategic way to use those products, while being mindful of regulations in place?

• Over what time horizon can full traceability of these resources be assured?

Figure 1. Raw material origins for global fishmeal and fish oil production in 2021.

Raising awareness on the value of by-products

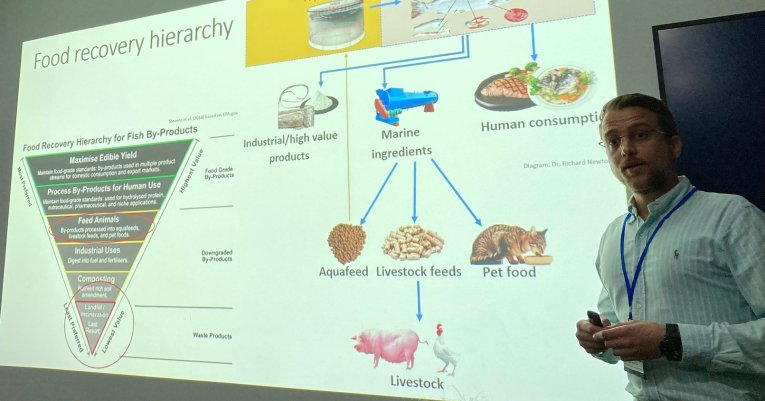

While the direct human consumption (DHC) market places a high nutritional value compared on the fillet of fish, a diverse and abundant range of nutrients remain within the by-products from fish processing. Aquaculture by-products provide opportunities of both a steady supply and usually centralized processing, giving them some advantages as a resource base. As we increase the volume of by-products produced from fisheries for human consumption and aquaculture, there could be a potential 15 million mt of additional ingredients, according to a 2016 report (Jackson & Newton, 2016). Current assessments suggest that this trend is already underway, with a well-established market place and policy landscape that is developing alongside, despite by-products being perceived as a lower value product and of inconsistent quality. Quality can markedly vary with changes in raw material, though clear progress has been made by the industry over the last twenty years in learning to better work with this raw material base to ensure more consistent production of high quality products. “We need to grow our understanding on how to use all of the fish we harvest, and identify those raw material flows involved to better understand our options for enhancing both production and product diversification”, according to Dr Brett Glencross, Technical Director at IFFO.

Wesley Malcorps

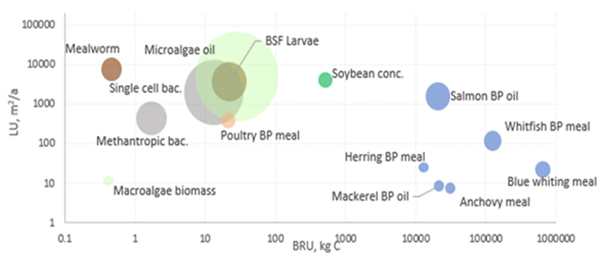

How do the various sustainability indicators fit in with the marine by-product ingredients narrative? How do by-products contribute to the sustainability story? “We need to balance the environmental, social and economic aspects, including carbon footprint” said Dr Wesley Malcorps, Postdoctoral Researcher at University of Stirling, Institute of Aquaculture. A relevant indicator here is the economic-Fish-in-Fish-out (eFIFO), which encourages the use of by-products by assessing their economic allocation to resource use. But we also need to look at parameters such as land use and biodiversity impacts, and biotic resource use. “The e-FIFO approach we’ve developed takes fluctuations around value of by-products into account” he explains. However, it is this economic allocation as applied to lifecycle assessment (LCA) that provides some really interesting contrasts (Figure 2). "Marine ingredients generally have a low carbon footprint, but this is not the whole story. Other impact categories are also important, like land use, freshwater use, use of biotic resources. There are many ways in which environmental burdens can be assessed ”, said Malcorps.

Figure 2. Contrast of various LCA impact categories (per tonne of ingredient) across different feed ingredients used in aquaculture feeds. Included are Biotic Resource Use (BRU), Land Use (LU) and relative Global Warming Potential (bubble size: scale not shown). Data from Newton et al. 2021.)

Traceability is a critical component of the by-product discussion. It is an assurance against adulteration of food, intra species feeding, contamination of feed. To advance traceability, a shared and secured network is needed between the users and suppliers of the data.

“We need a system to maintain the chain of custody all the way through” Katherine Bryar, Global Marketing Director at BioMar voiced. Many of the feed companies are highlighting circular economy principles as a key part of their sourcing criteria going forward. “We seek to decouple feed supply chains from directly competing with food for human consumption” said Bryar. But it is not just the feed companies calling for circular ingredients that is driving this burgeoning part of the marine ingredients sector.

“We see more and more of the fish going to direct human consumption. Presently 60% of our fishmeal and fish oil come from by-products” Arnt Ove Kolås, COO Feed at Pelagia explained. “How can we make the most of these resources?” was Kolås’ call. Increasing how much processing is done close to fishing ground and utilizing the whole fish for both feed and human grade oil are part of Pelagia’s core strategy, with the main challenge being on the fishing vessels. “Ideally, we need to keep the stick water, where a lot of value is, in the final product and capture that part of the product before it is wasted. When fishery products are processed at sea, this valuable resource is often lost”. With Blue Whiting, Pelagia is looking at value-adding the product further to make protein concentrates by removing the ash content. By separating the raw material into its different components, we can be more strategic in how we use different products. “We are paid based on the pro-rata of the protein content (fishmeal) and EPA+DHA content (fish oil) of our products. To ensure that the relative protein volume increases, we separate fish bone and skin from the meal raw material. To ensure that relative EPA+DHA volume increases, we refine fish oil by removing the parts we are not getting paid for. The future will belong to those that are able to utilize and get paid for the individual properties of the different parts of the fish. This is how we maximise the value of every fish”, said Kolås.

Arnt Ove Kolås, Katherine Bryar, Lahsen Ababouch, Melanie Siggs

Data-tracking is improving

Certification programmes are one of the many tools available to provide assurances regarding responsible sourcing and production of materials, acting as a bridge between fisheries and aquaculture, food and feed. They are also a powerful market driver. Chain of custody standards ensure that products are traceable from origins. Inclusion of by-products is both an opportunity and a challenge: “Data tracking for by-products is complex”, Dr Emily McGregor, Fisheries manager at MarinTrust explained: “Full traceability of single-species marine ingredients is more feasible. In version 3 of our Factory Standard, to be applicable in 2024, we’ll be paying a lot of attention to IUU risk for by-products – reliability and stability of indicators. The long-term aim is to be able to verify the stock. There are still additional checks at the factories to ensure they have the documentation to verify the source”. More than 240 assessments of by-products from around 20 countries, are currently MarinTrust approved (including species and stocks). “Traceability is part of our core focus, with the development of Key Data Elements (KDEs) and Critical Tracking Events (CTEs) with The Global Dialogue on Seafood Traceability (GDST). We are striving for balance: we need to balance how far we go with data to provide assurance and accessibility”.

Certification programmes are one of the many tools available to provide assurances regarding responsible sourcing and production of materials, acting as a bridge between fisheries and aquaculture, food and feed. They are also a powerful market driver. Chain of custody standards ensure that products are traceable from origins. Inclusion of by-products is both an opportunity and a challenge: “Data tracking for by-products is complex”, Dr Emily McGregor, Fisheries manager at MarinTrust explained: “Full traceability of single-species marine ingredients is more feasible. In version 3 of our Factory Standard, to be applicable in 2024, we’ll be paying a lot of attention to IUU risk for by-products – reliability and stability of indicators. The long-term aim is to be able to verify the stock. There are still additional checks at the factories to ensure they have the documentation to verify the source”. More than 240 assessments of by-products from around 20 countries, are currently MarinTrust approved (including species and stocks). “Traceability is part of our core focus, with the development of Key Data Elements (KDEs) and Critical Tracking Events (CTEs) with The Global Dialogue on Seafood Traceability (GDST). We are striving for balance: we need to balance how far we go with data to provide assurance and accessibility”.

It is hoped that European Union (EU) definitions will help standardize terms and calculation methodology for the industry. Standardisation and interoperability are key challenges to be considered.

Cultural habits and capacity building play a big role

In some specific countries, it is also the economics and infrastructure that are a challenge. An example of Northwest Africa was presented by Lahsen Ababouch, advisor to the FAO, who explained that the Moroccan authorities are aiming for zero waste, relying on a very active research institute based in Agadir. “The challenge is huge, with 469 processing plants, producing 184,000 mt of fishmeal and 36,000 mt of fish oil. We have improved the value in extraction from processing and now all the by-products go into fishmeal and fish oil. This industry is concentrated in just two cities which make logistics easier. To move this on, we need policies that incentivize the use of by-products from feed and food. Raising awareness on the nutritional attributes of by-products is imperative”. The involvement of an active research program and government support provided a good example of how the right support on the right issue could help deliver big impacts for both industry and government.

The cultural aspect of the food habit is very important. People in Togo and Senegal eat around 35kg/capita/year. However, fish consumption is less than 7kg/capita/year in Mauritania (while current fish stocks would allow an annual per capita consumption to reach 25kg), and it is around 13 kg/capita/year in Morocco. There is a clear divide in consumption habits between north and sub-Saharan west Africa.

In Mauritania, it is clear that food habits do not really include fish, but Senegal it is the opposite with large direct consumption of fish, Lahsen Ababouch explains. “Women are often in charge of the trade once the fish are landed, they are usually very well organized to use by-products to produce feed and then other options for direct human consumption”.

Disposal at landfills is very costly. This was the first driving force behind efforts being carried out in another project in Barbados to drive towards zero food waste. This project was implemented by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), and funded by the EU with financial support from the Moroccan government and the industry.

Melanie Siggs, Advisor to the World Economic Forum’s Friends of Ocean Action, turns to their Namibian case study. In that scenario the processing plants there are mostly in one location, where all the vessels land, fishing from the MSC hake fishery, shipping to Europe and North America. The aim is to use 100% fish, right now about 1/3 of the wild caught fish biomass is lost, mostly being discarded at sea. The project was funded by the UK government (DEFRA) and based on four pillars:

- whole fish paradigm (being accountable for all parts of the fish)

- enabling conditions (making 100% fish utilization easier, such as with an integrated sector, the President is on the high-level panel so there is political will)

- creating clusters (using Icelandic model to unify the industry)

- measuring research markets (work out what you’ve got, what are its properties and the markets)

The project funding ends next year and the cluster hopes to continue the project, to ensure long term durability. “We’ve created an ‘ask’ of 5 commitments for all the CEO’s in the cluster and two reports have been published to share good practices and raise awareness ” she concludes.

The role of feed producers in incentivising the whole value chain

Katherine Bryar, Global Marketing Director at BioMar, is convinced that the feed producers have a key role to play in driving positive changes: “Circularity is one of the components of our strategic approach to sustainability”, she explains. “Circular ingredients include secondary ingredients from direct human consumption processing. We look at the main products and the and co-products, including by-products and waste streams. We are trying to get rid of the traditional ‘waste’ language and focus on circular instead”. BioMar has developed its “BioSustain Impact Parameters”, with the aim of reducing their forage fish dependency ratio (FFDR): “This is a market demand solely, consumers believe that oceans are depleted. The consumer world is moving beyond offsetting, the younger generation want information and transparency”.

Arnt Ove Kolås, Brett Glencross, Jorge Diaz Salinas

Skretting aims to have 100% of its marine ingredients use by 2025 coming from certified sources. “If certifications are not available, then we are making sure those by-products we use are not from IUU“, Jorge Diaz Salinas, Sustanability Manager, indicated. He presented a clear decision framework that was being implemented by Skretting in its sourcing of marine ingredients from whole-fish, as well as by-products from both aquaculture and wild fish catch scenarios.

Dave Robb

As for Cargill AquaNutrition, it uses by-products as about 30% of their company fishmeal inclusion. The inclusion of fishmeal in warm water feeds is lower, but the proportion of it being from by-products is much higher. “We are working on broadening our (feed ingredient) basket without entering into competition on an existing material. The risk of contaminants in by-products means that we can’t use everything, but they have an advantage in that they can be treated when used as an ingredient. Driving innovation to maintain freshness and reduce waste is imperative” Dave Robb, Sustainability Manager explained.

There is a global movement towards zero food waste, and by-products are a key part of this strategy. This also fits well into the feed producers’ product diversification strategy. Consensus is being built so that the value of by-products is better understood and communicated. Modelling of those flows will be improved through a traceability system, but much can already be done by examining the various fishery and aquaculture resources flows. “Innovation underpins further progress in terms of processing infrastructure, interoperable systems and product diversification, the future is looking very circular”, Brett Glencross concluded.